Ciudadanía movilizada: motivos, emociones y contextos

Mobilized citizenship: motives, emotions and context

Abstract (en)

Recently, many mobilisations have emerged all around the world and their impact on social change has been noteworthy. In this paper we shall review the evolution of the latest models of collective action in order to better understand current challenges in the field of political protest. Scholars have suggested that identity, grievances, efficacy, and anger are the relevant motives for prompting action. Nonetheless, there is still some room for improvement. In addition to previous variables, there is enough argumentation to include others which have been overlooked by the hegemony of instrumental logic; we are talking about moral obligation and positive emotions. There is a deontological logic in collective protest that can explain why individuals do not simply participate to obtain some kind of benefit; they may also feel morally obligated to do so. Moreover, positive emotions, such as hope, pride or optimism, can reinforce motivation. Another important aspect is the role of context. The specific characteristics of the political and the mobilising context may differently activate some motives or others. All these new contributions question the hegemony of the instrumental logic and demand an update of the theoretical approaches. The authors discuss the implications for theory and future research on collective action.

Abstract (es)

Recientemente han surgido muchas movilizaciones por todo el mundo y su impacto a la hora de producir el cambio social es de destacar. En este artículo haremos una revisión de cómo han evolucionado los últimos modelos de acción colectiva para poder entender mejor los retos contemporáneos en el campo de la protesta política. Los motivos más relevantes señalados por la literatura científica para la promoción de la acción son: la identidad, la injusticia, la eficacia y la ira. Sin embargo, todavía quedan aspectos por mejorar. Además de las variables mencionadas, hay argumentos suficientes para incluir otros factores que han sido pasados por alto en la hegemonía de la lógica instrumental; hablamos de la obligación moral y de las emociones positivas. Hay una lógica deontológica en la protesta colectiva que puede explicar porqué los individuos no participan simplemente para obtener algún tipo de beneficio, sino que también pueden sentirse moralmente obligados a hacerlo. Más aún, las emociones positivas tales como la esperanza, el orgullo y el optimismo pueden reforzar la motivación. Otro aspecto importante es el papel del contexto. Las características específicas del contexto político y de movilización pueden activar diferencialmente algunos motivos u otros. Todas estas nuevas contribuciones cuestionan la hegemonía de la lógica instrumental y demandan una actualización de las aproximaciones teóricas. Los autores discuten las implicaciones para la teoría y la investigación futura sobre la acción colectiva.

References

Alberici, A. I., Milesi, P., Malfermo, P., Canfora, R. & Marzana, D. (2012, october). Comparing social movement and political party activism: the psychosocial predictors of collective action and the role of the Internet. TAISP Conference. University of Kent: Canterbury.

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In W. Kurtines & J. Gewirtz (eds.). Handbook of moral behavior and development, 1, 45-103. Hillsdale, N. J.:Lawrence Erlbaum.

Barnes, S. H. & Kaase, M. (1979). Political action. Mass participation in five western democracies. USA: Sage Publications.

Bar-Tal, B., Halperin, E. & de Rivera, J. (2007). Collective emotions in conflict situations: Societal implications. Journal of Social Issues, 63, 441-460.

Culver, J. L., Carver, C. S. & Scheier, M. F. (2003). Dispositional optimism as a moderator of the impact of health threats on coping and wellbeing. In R. Jacoby & Keinan, G. (eds.). Between stress and hope. From a disease-centered to a health-centered perspective, 27-55. Connecticut: Praeger.

Dinerstein, A. C. & Deneulin, S. (2012). Hope movements: Naming mobilization in a post-development world. Developmente and Change, 43, 585-602.

Drury, J. & Reicher, S. (2009). Collective psychological empowerment as a model of social change: researching crowds and power. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 707-725.

Duncan, L. E. & Smith, C. (2012). The psychology of collective action. In k. Deaux & M. Snyder (eds.). Oxford handbook of personality and social psychology, 754-781. New York: Oxford University Press.

Etzioni, A. (1970). Demonstration democracy. New York: Gordon & Breach.

Eyerman, R. (1998). La praxis cultural de los movimientos sociales. In P. Ibarra & B. Tejerina (eds.). Los movimientos sociales. Transformaciones políticas y cambio cultural, 139-163. Madrid: Editorial Trota.

Gamson, W. A. (1992). Talking politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis. An essay on the organization of experience. Boston, M. A.: Northeastern University Press.

Gómez-Román, C. & Sabucedo, J. M. (2014). The importance of political context: Motives to participate in a protest before and after the labor reform in Spain. International Sociology, 1-16.

Goodwin, J., Jasper, J. M. & Polleta, F. (2000). The return of the repressed: The fall and rise of emotions in social movement theory. Mobilization: An International Journal, 5, 65-83.

Hornsey, M. J., Blackwood, L., Louis, W., Fielding, K., Mavor, K., Morton, T., o’Brien, A., Paasonen, K., White, K. M. & White, K. M. (2006). Why do people engage in collective action? Revisiting the role of perceived effectiveness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 1701-1722. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00077.x.

Jarymowicz, M. & Bar-Tal, D. (2006). The dominance of fear over hope in the life of individuals and collectives. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 367-392.

Jasper, M. J. (1997). The art of moral protest. Culture, biography and creativity in social movements. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Jiménez, M. (2011). La normalización de la protesta. El caso de las manifestaciones en España (1980-2008). Catálogo de Publicaciones de la Administración General del Estado, (70). Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Kemper, T. D. (1991). Predicting emotions from social relations. Social Psychology Quarterly, 54, 330-342.

Klandermans, B. (1984). Mobilization and participation: social-psychological explanations of resource mobilization theory. American Sociological Review, 49, 583-600.

Klandermans, B. (1997). The social psychology of protest. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Klandermans, B. (2003). Collective political action. In D.O Sears, L. Huddy & R. Jervis. Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, 670-709. N. Y.: Oxford University Press.

Klandermans, B. (2014). Identity politics and politicized identities: Identity processes and the dynamics of protest. Political Psychology, 35, 1-22.

Kriesi, H. (1993). Political mobilization and social change: The Dutch case in comparative perspectiva. England: Avebury, Aldershot.

Le Bon, G. (1983). Psicología de las masas. Madrid: Morata (original, 1895).

Mannarini, T., Roccato, M., Fedi, A. & Rovere, A. (2009). Six factors fostering protest: Predicting participation in locally unwanted land uses movements. Political Psychology, 30, 895-920.

Martín-Baró, I. (1998). Psicología de la liberación. Madrid: Trotta.

McCarthy, J. D. & Zald, M. (1976). Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A partial theory. American Journal of Sociology, 82, 1212-1241.

Meyer, D., & Tarrow, S. (1998). The social movement society: Contentious politics for a new century. Boulder, C. O.: Rowman & Littlefield.

Opp, K. D., Voss, P. & Gern, C. (1995). Origins of a spontaneous revolution: East Germany, 1989. Ann Arbor: The Univesity of Michigan Press.

Páez, D. Javaloy, F., Wlodarczyk, A., Espelt, E. y Rimé, B. (2013). El movimiento 15-M: sus acciones como rituales, compartir social, creencias, valores y emociones. Revista de Psicología Social, 28, 19-33. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1174/021347413804756078.

Páez, D., Rimé, B., Basabe, N., Wlodarczyk, A. & Zumeta, L. (2015). Psychosocial effects of perceived emotional synchrony in collective gatherings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108, 711-729. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000014.

Peterson, A., Wahlström, M., Wennerhag, M., Christancho, C. & Sabucedo, J. M. (2012). May day demonstrations in five European countries, Mobilization, 17, 281-300.

Rimé, B. (2012). La compartición social de las emociones. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwe.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. N. Y.: Free Press.

Runciman, W. G. (1966). Relative deprivation and social justice: A study of attitudes to social inequality in twentieth-century England. Berkeley, C. A.: University of California Press.

Sabucedo, J. M., Durán, M. y Alzate, M. (2010). Identidad colectiva movilizada. Revista de Psicología Social, 25, 189-201.

Sabucedo, J. M., Grossi, J. y Fernández, C. (1998). Los movimientos sociales y la creación de un sentido común alternativo. En P. Ibarra y B. Tejerina (eds.). Los movimientos sociales. Transformaciones políticas y cambio cultural, 165-180. Madrid: Editorial Trota.

Sabucedo, J. M. & Vilas, X. (2014). Anger and positive emotions in political protest. Universitas Psychologica, 13, 829-838.

Sears, D. O., Huddy, L. & Jervis, R. (2003). Oxford handbook of political psychology. USA: Oxford University Press.

Simon, B., & Klandermans, B. (2001). Politicized collective identity. A social psychological analysis. American Psychologist, 56, 319-331.

Skitka, L. J. (2010). The psychology of moral conviction. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 267-281.

Skitka, L. J., Bauman, C. W. & Sargis, E. G. (2005). Moral conviction: Another contribution to attitude strength or something more? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 895-917.

Smith, E. R. (1993). Social identity and social emotions: Toward new conceptualizations of prejudice. In D. M. Mackie & D. L. Hamilton (eds.). Affect, cognition, and stereotyping: Interactive processes ingroup perception, 297-315. San Diego, C. A.: Academic Press.

Stürmer, S., & Simon, B. (2004). Collective action: Towards a dual pathway model. European Review of Social Psychology, 15, 59-99.

Stürmer, S. & Simon, B. (2009). Pathways to collective protest: calculation, identification, or emotion? A critical analysis of the role of group-based anger in social movement participation. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 681-705.

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & G. William (eds.). Austin psychology of intergroup relations, 7-24. Chicago: Nelson- Hall.

Tangney, J., Stuewig, J. & Mashek, D. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behaviour. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345-372.

Tanner, C., Medin, D. L. & Iliev, R. (2008). Influence of deontological versus consequentialist orientations on act choices and framing effects: When principles are more important than consequences. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 757-769.

Turner, J. C. & Killian, L. M. (1987). Collective Behaviour (3rd. ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N. Y.: Prentice Hall.

Van Aelst, P. & Walgrave, S. (2001). Who is that (wo)man in the street? From the normalization of protest to the normalization of the protester. European Journal of Political Research, 39, 461-486.

Van Stekelenburg, J. & Klandermans, B. (2010). The social psychology of protest. Sociopedia. isa, 1- 13.

Van Stekelenburg, J., Klandermans, B. & van Dijk, W. (2009). Context matters: Explaining how and why mobilizing context influences motivational dynamics. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 815-838. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01626.x.

Van Stekelenburg, J., Klandermans, B. & van Dijk, W. W. (2011). Combining motivations and emotion: The motivational dynamics of protest participation. Revista de Psicología Social, 26, 91-104. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1174/021347411794078426.

Van Stekelenburg, J., Walgrave, S., Klandermans, B. & Verhulst, J. (2012). Contextualiszing Contestation. Framework, desing and data. Mobilization, 17, 249-262.

Visitas

Downloads

How to Cite

Mobilized citizenship:

motives, emotions and context

Ciudadanía movilizada:

motivos, emociones y contextos*

Xiana Vilas**, Mónica Alzate***, José Manuel Sabucedo**

* Artículo de investigación.

(doi: https://doi.org/10.15332/s1794-9998.2016.0002.01)

** Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, España. Correspondencia: Xiana Vilas, Dirección postal: Departamento de Psicoloxía Social, Básica e Metodoloxía. Facultade de Psicología, 15782 Campus Vida, Santiago de Compostela, España.

Correo electrónico:

[email protected];

[email protected].

*** Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó, Medellín, Colombia

[email protected]

Agradecimientos: Secretaría de Estado de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación. Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad. PSI2012-31667

Recibido: 2 de febrero de 2016 / Revisado: 13 de marzo de 2016 / Aceptado: 3 de mayo de 2016

Abstract

Recently, many mobilisations have emerged all around the world and their impact on social change has been noteworthy. In this paper we shall review the evolution of the latest models of collective action in order to better understand current challenges in the field of political protest. Scholars have suggested that identity, grievances, efficacy, and anger are the relevant motives for prompting action. Nonetheless, there is still some room for improvement. In addition to previous variables, there is enough argumentation to include others which have been overlooked by the hegemony of instrumental logic; we are talking about moral obligation and positive emotions. There is a deontological logic in collective protest that can explain why individuals do not simply participate to obtain some kind of benefit; they may also feel morally obligated to do so. Moreover, positive emotions, such as hope, pride or optimism, can reinforce motivation. Another important aspect is the role of context. The specific characteristics of the political and the mobilising context may differently activate some motives or others. All these new contributions question the hegemony of the instrumental logic and demand an update of the theoretical approaches. The authors discuss the implications for theory and future research on collective action.

Keywords: Collective protest, moral obligation, identity, positive emotions, efficacy, context.

Resumen

Recientemente han surgido muchas movilizaciones por todo el mundo y su impacto a la hora de producir el cambio social es de destacar. En este artículo haremos una revisión de cómo han evolucionado los últimos modelos de acción colectiva para poder entender mejor los retos contemporáneos en el campo de la protesta política. Los motivos más relevantes señalados por la literatura científica para la promoción de la acción son: la identidad, la injusticia, la eficacia y la ira. Sin embargo, todavía quedan aspectos por mejorar. Además de las variables mencionadas, hay argumentos suficientes para incluir otros factores que han sido pasados por alto en la hegemonía de la lógica instrumental; hablamos de la obligación moral y de las emociones positivas. Hay una lógica deontológica en la protesta colectiva que puede explicar porqué los individuos no participan simplemente para obtener algún tipo de beneficio, sino que también pueden sentirse moralmente obligados a hacerlo. Más aún, las emociones positivas tales como la esperanza, el orgullo y el optimismo pueden reforzar la motivación. Otro aspecto importante es el papel del contexto. Las características específicas del contexto político y de movilización pueden activar diferencialmente algunos motivos u otros. Todas estas nuevas contribuciones cuestionan la hegemonía de la lógica instrumental y demandan una actualización de las aproximaciones teóricas. Los autores discuten las implicaciones para la teoría y la investigación futura sobre la acción colectiva.

Palabras clave: protesta colectiva, obligación moral, identidad, emociones positivas, eficacia, contexto.

Social mobilization is on the rise and has become commonplace all over the planet. Arab Spring, Anti-austerity movements, Occupy and "Refugees Welcome" movement are some examples of the latest movements. The World Values Survey (1981 -2008) shows that 15.8 % of participants, at some time, attended peaceful demonstrations and 35.3 % would be willing to do so at some stage. This increase in citizen participation, particularly in Western societies, is known as the protest normalization process (Barnes & Kaase, 1979; Etzioni, 1970). This process is an indicator of democratization of protest and shows how it has been transformed into a repertoire for demanding changes or expressing indignation (Meyer & Tarrow, 1998).

There is another associated phenomenon alongside the normalization of protest, the normalization of the protester (van Aelst & Walgrave, 2001), which goes hand in hand with the former, and is related with the diversification of the actors involved. This means that the practice of these phenomena has extended to increasingly broader sections of the population (Barnes & Kaase, 1979; Jiménez, 2011). Thus, mobilization is no longer confined to a specific sector, as was previously the case: young, well-educated, left-wing people and mainly men. Socio-demographic variables are losing significance. Women, the elderly and individuals of right-wing tendencies are increasingly joining this kind of political participation (Jiménez, 2011). Clearly, there are still socio-demographic differences, but they are no longer so relevant and they vary from one country to another.

As these variables are devalued, the differences existing between participants and the general population lessen, thus increasing the probability that an individual, from any social sector, may opt for this kind of behaviour. This leads us to assert that there are other motives, beyond the merely sociodemographic variables, which are having a bearing on participation. We are referring to the psychosocial motives for collective action. In this article we include the classical variables of protest, the moral obligation variable and the positive emotions, which have shown their relevance in recent research. We also attempt to overcome the existing limitations of the psychosocial proposals of collective action considering that the new models need to be extended. Our main contribution is to show how the new variables work in political protest and to update the role of the classical ones.

Psychosocial approach

Social psychologists have focused their attention on the collective protest, owing not only to its recurrent appearance in the daily life of citizens, but also to the level of its political and social influence. Some examples are the Arab Spring, with the overthrowing of governments in Egypt and Tunisia; and the spanish movement Indignados that promote the foundation of the new party Podemos. Nonetheless, there are also other more subtle ways of bringing about social change. Social movements place certain issues within the political agenda (Walgrave & Vliegenthart, 2012), democratize participation, invigorate our societies (Simon & Klandermans, 2001) and facilitate social change (Drury & Reicher, 2009).

Through mobilization, citizens challenge the authorities; they express their non-conformity with the established norms and values, and question the existing power relations (Sabucedo, Grossi & Fernández, 1998). Therefore, protesters are social actors capable of altering the reality in which they are immersed. Most frequently, collective action seeks to exert some kind of influence over social, economic and political rights; thus the increasing interest from social scientists. However, not only does political activism have an impact on a social level. Participating in social mobilizations also has an impact on the individual, as usually involvement in protests increases the level of wellbeing (Klar & Kasser, 2009; Páez, Rimé, Basabe, Wlodarczyk & Zumeta, 2015).

As the citizen is an actor who perceives and interprets reality; social mobilization is the result of a certain way of perceiving and constructing reality in a collective manner (Eyerman, 1998). People in similar situations may respond in very different ways on the basis of how the context is interpreted. Indeed, social reality is neither fixed nor objective: it is constructed on the basis of interaction between the different discourses flowing through society (Sabucedo et al., 1998). For instance, confrontations and negotiations between the different social agents acquire relevance in establishing a certain status quo. The role of collective action is essential in these confrontations, discourses which previously were marginal, such as feminism or environmentalisms, now form part of the concerns of today's societies.

The way of approaching these phenomena from a psychosocial perspective is by relating two aspects of reality, subjective aspects (psychological) and social or structural aspects (van Zomeren, Postmes & Spears, 2008). Therefore group perceptions, feelings and behaviours are examined linking them with the social context (van Stekelenburg & Klandermans, 2010).

The principal aim of this work is to explore the evolution of the main models of collective action over the different decades to the present and, from there, to integrate the psychosocial motives with the new proposals. We seek to put together the different classical variables of a cognitive and emotional nature with more recent ones, such as moral obligation and positive emotions. Moreover, in this proposal, it is essential to take into account the contextual variations that have a bearing on the motivational dynamics.

From irrationality to the resource mobilization theory

The initial approaches of crowd theories implied an irrational approach to collective behaviours (Le Bon, 1983). From these sociological theories, protest was caused by a disturbed crowd, victim of an emotional contagion, and its actors were devoid of any rational analysis. The relative deprivation theory (Runciman, 1966) did not help to change this irrationalist view of the actor, given that it focused excessively on dissatisfaction and frustration. Not until the advent of the resource mobilization theory was it possible to overcome this irrationalist conception. From this theory, it is postulated that mobilization will depend on citizens' resources (human, material and structural) and on demand (McCarthy & Zald, 1977). People will mobilize depending on whether they have the resources necessary to do so and whether there is a real demand for mobilization. This approach alludes to objective factors and succeeds in rationalizing the motives for protest.

The merit of this approach is that it overcomes the irrationalist spirit of crowd theories and it incorporates aspects of great interest. Resources and organization are clearly relevant elements for the success of a mobilization, but this analysis becomes excessively reductionist by ignoring the characteristics related with the social agents involved (Sabucedo et al., 1998). Klandermans (1984) proposes a more subjective version, from a socio-psychological point of view, suggesting that the important thing is not the objective situation in which a group finds itself, rather how this is interpreted. It is not enough for a group to be in a situation of injustice, rather that the situation be perceived as such. The approach of Klandermans (1984) is a psycho-social extension of the resources mobilization theory and is represented by the individuals' subjective cost-benefit calculations. The motivation to participate would be the result of the value the individual assigns to a specific goal, and of the expectation of attaining it through a given collective protest. Consequently, this approach defends an instrumental path towards political action, singling out efficacy as a core element.

From the collective action frames theory to the renewal of the classical variables

The theory of collective action frames (Gamson, 1992), which is based on the notion of the symbolic construction of reality, proposes the frame concept put forward by Goffman (1974). Frames are interpretative schemes laid over the reality.

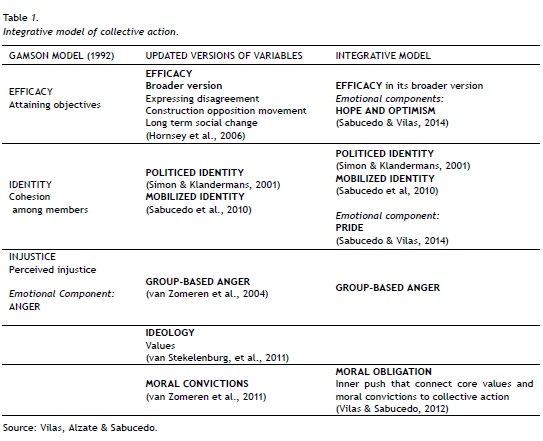

Indeed, active minorities endeavour to disseminate alternative visions of reality and challenge the dominant social discourses (Sabucedo et al., 1998). Gamson propounds the existence of three frames that motivate collective political action: injustice, identity and efficacy. The injustice frame is made up of a cognitive component and an emotional one (grievances and anger, respectively). Currently, we can consider these four components: grievances, anger, identity and efficacy, as the classic variables of protest; and not only owing to the attention received in recent years, but also due to the empirical support they have been receiving (Stürmer & Simon, 2004; van Zo-meren et al., 2008). Hence we consider it is essential to mention the important legacy left by Gamson. We will explain these variables in more detail, showing how they have evolved over time and their reformulations.

Grievances

According to Gamson this is the cognitive element of injustice frame. This approach to collective action originates from the relative deprivation theory (Runciman, 1966). Individuals become involved in collective actions when they feel that they are the objects of injustice or group grievances. Grievances are at the heart of every protest (van Stekelenburg & Klandermans, 2010); and they are usually the first step towards triggering action. Among these possible injustices, Klandermans (1997) mentions illegitimate inequality, suddenly imposed grievances and violated principles. Nonetheless, grievances and social injustices are not sufficient to trigger mobilisations on their own. It can be argued that there is no shortage of grievances around the world, but they are too general and persistent for us to be able to predict collective protest. Other elements to explain protest participation are required.

Anger

Emotions were neglected for many years, as they were seen as a threat which could topple the rationalist hegemony of the period (Goodwin, Jasper & Polleta, 2000). Gamson was among the first, after irrational theories, to propose an emotion-based explanation. He noted that anger constituted a key element for the injustice frame, since this depends on "the righteous anger that puts fire in the soul and iron in the belly" (1992, p. 32). This is the principal emotion analyzed to explain protest, and it has been shown to have an important bearing on the motivational dynamics of participants (van Zomeren et al., 2008; van Zomeren, Spears, Fischer & Leach, 2004). This emotion is associated to the injustice frame, and emerges when certain principles are violated or when an unjust situation becomes apparent. In its most updated version, van Zomeren et al. (2004) conceptualized anger on the group level: group-based anger. In the intergroup emotion theory (Tajfel, 1981; Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Smith, 1993) group identification is a key element for the emergence of group emotions.

Van Zomeren combines the relative deprivation theory (Runcinman, 1966) and the intergroup emotion theory (Smith, 1993). From relative deprivation, he assumes that people not only perceive injustice, but from it they also derive the emotional response of anger. Moreover, in collective protest, emotions are interpreted on the basis of the group; this perception of inequality or injustice is collective, and thus the emotional response will be so. The greater the identification with the group, the greater the possibility that anger will appear when the group is threatened, and therefore the greater the probability of involvement in protest.

Identity

When researchers turned their attention to the social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner & Killian, 1987) it was a logical step, because if anything characterizes protest activities, it is that individuals do not act on their own; rather they do so collectively. This involves shifting from an "I" to a "we", which entails assuming that a group of individuals share a common problem and, in order to solve it, they need to act jointly and not individually. Tajfel (1981) identified this question perfectly when differentiating between the strategies of social change and social mobility.

In recent studies on collective protest of all kinds of identity, it is politicized identity which has the greatest bearing on motivation. According to Klandermans and Simon (2001), the perception that there is a third group to be persuaded in order to win over sympathizers, along with the group awareness of experiencing an unjust situation means that the collective identity is politicized. The impact of identity will be greater when identification comes about with groups whose objective is to act in defence of the interests and demands of this group (Sabucedo, Durán & Alzate, 2010; Simon & Klandermans 2001). It is this identity which has an influence on how people perceive the social world and which induces individuals to act on the same. When identity is politicized, people assume that their circumstances depend on the power relations with other groups and that only through political action can they be modified.

But it is necessary to differentiate between politicization and mobilization (Sabucedo et al., 2010). The second is not possible without the first, but the first not inexorably leads to the second. For this reason we propose the mobilized identity. When Klandermans and Simon talk about politicized identity they assume that political consciousness and mobilization are part of the same reality. They include both the process by which subjects are aware that a situation depends on a specific political context and their intention to engage in it. We propose that the term politicized identity should be reserved for the process by which people place their collective identity in the political context and in the struggle with other identities. However, as we have shown above, it is necessary to distinguish these two moments. In this manner, we postulate that after the politicized identity appears mobilized identity. We consider that mobilized identity is connected to the necessity to undertake political action to seek alternatives and outputs for the group.

Efficacy

Efficacy refers to the expectations that a collective action may modify a situation that is adverse for the in group (Gamson, 1992). From a theoretical perspective, the instrumentality variable has two important advantages: firstly, and given that these actions are carried out in the belief that they will be successful, the rational image of human behaviour is reinforced; secondly, and instead of evaluating possible antecedent factors for these activities (e.g. the characteristics of participants), this variable focuses directly on ascertaining how the efficacy of a specific action for attaining a desired objective is perceived. Different studies have evinced this variable's close relationship with participation in protests (Klandermans, 1984; Stürmer & Simon, 2004; van Zomeren et al., 2004; van Zomeren et al., 2008). Although it has been predominant in recent models, it is starting to be doubted as it is currently perceived.

There are studies (van Stekelenburg, Klandermans & van Dijk, 2009; Vilas, 2010; Vilas & Sabucedo, 2012) that leave the door open to the debate on the relevance of instrumentality in protest. In these studies efficacy is shown to have no impact when predicting the motivation for participation in value-orientated demonstrations. As there are considerable gaps in its conceptualization; a broader extension of the term is required. Hornsey et al. (2006) argue that efficacy, in its most classical concept, understood as the expectation success for a specific political action has a limited role. Therefore there is a need to reformulate this concept. For example, Hornsey et al. (2006) incorporate into its conceptualization: the expression of disagreement, the construction of an opposition movement and the expectations of long term social change.

The last models of collective action

The most recent versions of these variables and the relationships between them are gradually acquiring more nuances and extending their capacity to explain collective behaviour in the last models of collective action. These are the models proposed by Stürmer and Simon (2004), the SIMCA model (Social Identity Model of Collective Action) by van Zomeren et al. (2008), and the model by van Stekelenburg, Klandermans and van Dijk (2011).

Stürmer and Simon (2004), proposed two different routes towards collective action which would act independently; they emphasise the components of identity and efficacy as the essential elements, and question the direct motivating power of anger that would have an indirect effect (Stürmer & Simon, 2009).

In the SIMCA model van Zomeren et al. (2008) link the functions of these variables with the social identity theory, this model predicts that on the basis of a relevant social identity, group-based anger and efficacy promote collective action (van Zomeren, Postmes & Spears, 2012).

Conversenly, van Stekelenburg, Klandermans and van Dijk (2011) highlight the need to incorporate the ideology variable. By ideology they refer to the set of values and beliefs that are important for individuals in order for them to mobilize when they perceive themselves to be threatened. The ideological path can be purposeful in maintaining moral integrity by voicing one's indignation whereas instrumentality path in solving a social or political problem (van Stekelenburg & Klandermans, 2010). These authors recognize the emerging interest in expressive motivations contrary to instrumental ones.

Van Zomeren, Postems & Spears (2011), incorporate the value of moral convictions. More specifically, they affirm that "moral absolutism is a 'hallmark' of moral motivation as it tolerates no violations and thus motivates a change of the current situation" (p. 167). Although they suggest moral concerns, these explanatory models allude to a specific group grievance: a moral violation. In the past, moral violations have been considered a form of group grievance (Klandemans, 1997; Kriesi, 1993). This is undoubtedly interesting in that, for the first time, the explanatory models for group action allude to a specific group grievance. However, from our point of view, moral convictions do not actually differ from a specific kind of perceived injustice.

In the present study we propose a different manner of analysing the relation of moral principles over political action, more related to a personal inner push to act according what it is morally right. We called this variable moral obligation (Vilas & Sabucedo, 2012).

New elements to integrate into the models of collective action

As we have seen, in recent years significant progress has been made in acquiring knowledge on the psycho-political variables related with participation. These models enjoy a certain degree of empirical support, but still we miss variables of interest in protest such as moral obligation and positive emotions. These variables will allow us to extend the theoretical corpus on grounds for protest, and to provide alternative explanations to the instrumental predominance over the years. It is also relevant to mention that the differences in the relationships between these variables may be due to the variations in the context where the action takes place; this will encourage scholars to have into account the social and political context.

Moral obligation

As we have said, there is another way of analyzing the relation of morality over political protest. After grievances or violated moral convictions people may feel obligated to act in accordance with their own moral values. We are referring to an inner push which motivates participation, the moral obligation component. Moral obligation is not the result of group pressure, of authority, of fear of punishment or the attainment of a reward; thus it is not an external obligation, but an inner obligation. Some aspects of this new proposal are indebted to a research line initiated by Skitka (Skitka, 2010; Skitka, Bauman & Sargis, 2005), which acknowledges the impact that moral convictions and values have on behaviour.

But the moral obligation to which we refer is a personal decision to participate in a specific collective action based on the belief that this is what must to be done; it is the psychological mechanism that connects the moral convictions to action. Action has to be done because that is what conscience dictates, what we "should" do. If the moral obligation means that individuals are somewhat impervious to external pressures, they will also be so to the results of their behaviours. It has been demonstrated that acting in accordance with one's beliefs contributes to our well-being by avoiding cognitive dissonance, increasing self-esteem, self-respect and recognition (Opp, Voss & Gern, 1995; Rokeach, 1973).

Along the same line, Bandura (1991) points out that "people do things that give them self-satisfaction and a sense of self-worth" (p. 69). Moral obligation will facilitate participation because one assumes that 'is what has to be done' and one feels satisfied in doing so". There is empirical evidence of the influence of this variable over motivation to participate (Vilas, 2010; Vilas & Sabucedo, 2012), and help to clarify why people sometimes get involved in protest despite the higher costs.

Positive emotions

As stated above, anger formed part of the principal explanatory models for collective action, and the importance thereof would seem to be indisputable. Nonetheless, there is no reason why people should participate solely because they are angry. There are emotions which are linked to the performance of an action and to the possibility of obtaining a desired objective. In the same way as injustice was not the only frame mentioned by Gamson, neither is anger the only emotion conducive to protest.

Recently there has been increasing interest in positive emotions in collective action (Páez et al., 2013; Sabucedo & Vilas, 2014), and one of those which has aroused most interest is hope. According to Jarymowicz and Bar-Tal (2006), hope is a complex emotion related with the expectation that desirable phenomena will occur. The anticipation that established objectives will be attainable activates hope. Hence, an emotional climate of hope facilitates targeted and sustained group activity in the future (Bar-Tal, Halperin & de Rivera, 2007). Páez et al. (2013) state that "effectiveness is associated to the propensity to feel inspired and to plan a better future" (p. 9). In this regard, we could be forgiven for thinking that if anger is the emotional component of the injustice frame, for the effectiveness frame it could be hope.

Another of the positive emotions, closely linked to hope, is optimism. This emotion would be linked with the expectations of positive results (Culver, Carver & Séller, 2003), and therefore would also be associated with the efficacy frame. Kemper (1991) linked these two emotions to the group and to the perceived status thereof, a perception which is highly relevant for social action (Duncan & Smith, 2012). Kemper alluded to optimism and hope as emotions connected to the anticipation of an improvement in status or power for the ingroup, motives which would lead to the group's involvement in the protest.

Pride is another emotion associated with collective protest (Goodwin, Jasper & Polleta, 2000). This is linked strongly with the group situation and the individual's relations with a group. The social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) shows us that individuals who are members of aggrieved groups and who feel highly identified with them will mobilise to change that state of affairs. When identity is politicized, individuals assume that the situation depends on power relations with other groups, and that it can only be modified through political action. Pride demands respect for the group. On the other hand, pride would also appear to be associated with the performance of actions which are highly valued in social terms (Tangney, Stuewig & Mashek, 2007). This emotion could thus be associated with the identity frame.

In view of the foregoing regarding hope, optimism and pride, it seems clear that positive emotions can also facilitate political protest (Sabucedo & Vilas, 2014). These can constructively channel anger and steer individuals towards action. This supposes that positive and negative emotions need not be incompatible, as was previously thought (Wolpe, 1958). On the contrary, both types of emotions may act jointly to activate participation. Emotions vary on the basis of the intergroup relations which arise at any given moment; accordingly, like many psychological processes, they are context dependent (Rimé, 2012). Emotions are thus going to depend on the meaning which individuals give to what happens around them (Lazarus, 1984). We have seen that there is a correspondence between emotions and cognitive processes in collective action when Gamson linked anger with perceived injustice; thus positive emotions such as hope and pride could be equally connected to the cognitive processes of perceived efficacy or collective identity.

Nowadays the understanding of collective action demands a new conception of the person. We propose an integrative model for collective action (table 1) where people are mobilized not only by consequentialist logic, but also by deontological orientations (Vilas & Sabucedo, 2012). The extended versions of the classical variables and the new ones are included in this model. We consider that this model open up a human being perspective more social and less instrumental. Emotions are group-based, for example anger is derived from a group-based injustice, and collective efficacy also implies the connection to the group. We incorporate the new variables such as positive emotions and moral obligation, which have shown relevance in explaining protest (Vilas & Sabucedo, 2012; Sabucedo & Vilas, 2014), and demand a new understanding of this behaviour.

This model emphasizes a more social and deontological human conception than the homo economics conception (van Zomeren & Spears, 2009). Those who attend to protests are not just angry people that pretend to attain some objectives, but they are a collective group with political awareness, that are proud of acting according their own principles and on behalf of the group.

However, all these variables do not have the same significance in every protest. We have to take into account that not all protests are equal, the circumstances around them determine which motives are more important. Thus the context should be included in the analysis of protest.

Context

One of the principal functions of social psychology is to relate the individual with the context. As the social and political context is particularly changeable, it is important to take this into account when determining the grounds for protest. Changes arise in supra-national settings (i.e. European economic crisis), in national settings (i.e. new laws, change of party in power) and in issues that concern citizens or which are in the current political agenda (i.e same-sex marriage, abortion, etc.). These scenarios may activate different motivations for citizens to take to the streets. In order to facilitate the study of context, van Stekelenburg, Klandermans and van Dijk (2009) have proposed two different kinds of contexts: mobilizing context and political context.

The mobilizing context would be the most immediate context in relation to the protest, and could be described in terms of demand and supply (Klandermans, 2003). Demand refers to the potential of protesters in a society and supply refers to the existence of groups or movements that can canalize these demands, and also their characteristics. Aspects which make up this mobilizing context include the subject of the protest and the convening organization. According to mobilizing context and Turner and Killian's proposal (1987) we could speak of at least two kinds of mobilization which have found empirical support: value-oriented protests, which would be those demonstrations concerning values where the ideology variable would predominate. And the other kind of mobilization would be power oriented-protests; referring to those demonstrations in which the aim of the protest is more focused on influencing policies, owing to which the core element would be efficacy (van Stekelenburg, Klandermans & van Dijk, 2009).

The other kind of context is the political context, and refers to the broader context in which the collective protest is immersed. Characteristics thereof include the current political climate, the political forces involved and political tension and conflict. These aspects could help us to reveal whether there are long-term objectives, such as wearing down the government. Recent studies (Peterson, Wahlström, Wennerhag, Cristancho & Sabucedo, 2012; Gómez-Román & Sabucedo, 2014) have shown that the national level is an important factor for understanding citizens' motivations in protest. A country's trade union model, the political stability of parties, the government's ideology, the economic situation, the proximity of elections or the degree of corporatism are factors which may have a bearing on reasons for participation. As behaviour does not take place in a social vacuum, scholars should incorporate the analysis of both mobilising and political context in the analysis of protest.

Conclusions

Collective protest is a form of political participation which is increasingly evident in citizens' current repertoire. In this work we have reviewed the principal psychosocial models and we have referred to the motives for participation proposed to date. We do not question these motives; rather we feel that they provide an incomplete picture of the reasons underlying collective action. To attempt to overcome these limitations, these models need to be extended, assuming that, in addition to the classical variables of efficacy, identity and anger, as proposed by Gamson, there are other types of variables.

One of the most interesting points that emerge from this work is related to the role of efficacy. We have seen how efficacy has enjoyed a prominent position in protest models, but recent studies demand a new way of understanding it. This new version of instrumentality would include other purposes beyond the immediate rewards, such as expressing disagreement, contributing towards constructing an opposition movement or achieving long-term social change. Individuals may participate considering a long-term instrumentality, or increasing cohesion among participants (Mannarini, Roccato, Fedi & Rovere, 2009); or even may have hidden political intentions. In the former case, it can be assumed that this specific action will be ineffective, but that the desired goal will be attained through sustained action. In the last cases, it should be borne in mind that the mobilization is not an isolated event; rather, it forms part of a more general group's dynamics and political dynamics. Hence, in future studies, in addition to enquiring about the efficacy of the specific action, we must ask about the instrumentality attributed to it in the long term, and also about other possible advantages that action may have in relation to the general political dynamics.

In this work we want to stress that beyond this consequentialist logic through which human beings operate, there is an ethical or moral logic (Tanner, Medin & Iliev, 2008). This logic operates outside the aforementioned one, and it has remained separate from protest motives. Individuals do not act solely to attain something; they also act to defend their strongest principles. In such cases, it would be the feeling of moral obligation that would lead citizens to protest. It should be taken into account that these two motives, instrumentality and moral obligation, are not opposites, rather they can act jointly. While it is true that in the absence of efficacy feelings of moral obligation must be strong in order to motivate participation.

In principle, it may seem strange for individuals to become involved in behaviours which are ineffective in attaining an objective. This will depend on the general political context. When this context is unfavourable, and individuals attempt to defend objectives which are important for their identity and which have a high emotional load, it is possible that instrumental logic (at least as it is habitually conceived) need not be a necessary factor for the action. The deontological logic is relevant since it enables us to incorporate the moral (and also rational) dimension of human beings, into the causes of participation. Still a lot of work has to be done related to this variable; it is especially relevant to go in depth into the moral obligation concept and to develop accurate measures.

Just as efficacy is gradually losing its central position within protest models, the motive of identity is gaining ground as one of the most essential (Klandermans, 2014; van Zomeren, Postmes, Spears, 2008). In more individualistic societies, the promotion of this identification is rarer. Duncan et al. (2012) explain that in the USA collective protest is somewhat more complicated, as this system assumes that the blame for injustices lies not with the political system but with the individual. In a society wherein individual interests take precedence over group interests, access to protests is hindered, owing to the lack of group cohesion as a cementing force. Hence, the organizations of movements must stress their capacity for acting collectively and, at the same time; attempt to transform collective identity into a collective politicized identity. In this way the organizers will achieve to overcome the systemic arguments that lay the blame on the individual (Duncan et al., 2012). Nonetheless, the process through which social identities are politicized is still unclear (van Zomeren, et al., 2008) and there is a need to continue outlining how they work in future research. Group awareness (Klandermans & Simon, 2001) would seem to be essential in this process; this awareness is strengthened when signalling an out-group as being responsible for the unjust situation, and stressing collective capabilities as opposed to individual ones.

This identity process also involves emotions given that in the area of protest these emotions are collective; they are group-based emotions (Smith, 1993; van Zomeren et al. 2004; Rimé, 2012). Anger has been the predominant emotion. Current models of collective action defend that individuals would participate in protests because they feel angry towards grievances or injustices. Conversely, in the study by Alberici et al. (2012), an activist acknowledges in an interview that: "... when I say 'anger', I mean positive anger... Such anger is positive because it drives me to do something to get rid of the mafia. So, such anger is not a destructive feeling". In this example we can see how anger may have a constructive character, and may be linked with emotions of a positive nature. Positive emotions can channel anger towards protest (Sabucedo & Vilas, 2014), and in turn generally provide individuals with well-being (Klar & Kaaser, 2009).

If hope is a fundamental motivational force for human beings (Dinerstein & Deneulin, 2012), we should also point out the demobilizing power that hopelessness would have. In this case, people assume that the state of affairs is given, and that nothing can be done to change it (Martín-Baró, 1998). Injecting hope can increase the expectations of success in a mobilisation, and is thus linked with the component of efficacy (Bar-Tal, 2006; Paez et al., 2013), but a long-term efficacy which enables sustained actions of time. Optimism and pride are emotions that can also be found in the activist's emotional spectrum. Strong positive group emotions must be taken into account, such as pride, that can be linked with feelings of moral superiority opposed to the opponents' immorality. In this field much still remains to be explored, hence the need to incorporate these emotions into future lines of research.

Another aspect to take into account in oncoming research is the role of context and the recognition of different moments of protest. We have already mentioned that context provides us with clues for ascertaining the weight of motives for participation. Taking into account different settings we can identify whether mobilizations have a more or less short term objective; whether they seek to change political proposals, to express values or to assert identities. In each case the motives for participation and the relations between them will be different. We should also take into account that social movement reality is made up of different moments. All the variables that we have seen play an important role in a moment of the collective protest behaviour. For example the perceived injustice and the identity feelings should come first than the moral obligation; we have already mentioned how positive emotions can canalize anger to push people to act, thus being anger first (Sabucedo & Vilas, 2014). To ascertain what these relationships are and in which moment of the protest appear more work is needed.

In short, in this study we have made progress towards the construction of an integrating social mobilization model which introduces significant changes with regard to the previous ones. Future research will include determining which elements are essential in the protest in each context and in each moment, providing a vision of the less instrumental but not necessarily less rational human being; and rendering it capable of also being mobilised by moral motives and through positive emotions.

References

Alberici, A. I., Milesi, P., Malfermo, P., Canfora, R. & Marzana, D. (2012, october). Comparing social movement and political party activism: the psychosocial predictors of collective action and the role of the Internet. TAISP Conference. University of Kent: Canterbury.

Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In W. Kurtines & J. Gewirtz (eds.). Handbook of moral behavior and development, 1, 45-103. Hillsdale, N. J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Barnes, S. H. & Kaase, M. (1979). Political action. Mass participation in five western democracies. USA: Sage Publications.

Bar-Tal, B., Halperin, E. & de Rivera, J. (2007). Collective emotions in conflict situations: Societal implications. Journal of Social Issues, 63, 441-460.

Culver, J. L., Carver, C. S. & Scheier, M. F. (2003). Dispositional optimism as a moderator of the impact of health threats on coping and well-being. In R. Jacoby & Keinan, G. (eds.). Between stress and hope. From a disease-centered to a health-centered perspective, 27-55. Connecticut: Praeger.

Dinerstein, A. C. & Deneulin, S. (2012). Hope movements: Naming mobilization in a post-development world. Developmente and Change, 43, 585-602.

Drury, J. & Reicher, S. (2009). Collective psychological empowerment as a model of social change: researching crowds and power. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 707-725.

Duncan, L. E. & Smith, C. (2012). The psychology of collective action. In K. Deaux & M. Snyder (eds.). Oxford handbook of personality and social psychology, 754-781. New York: Oxford University Press.

Etzioni, A. (1970). Demonstration democracy. New York: Gordon & Breach.

Eyerman, R. (1998). La praxis cultural de los movimientos sociales. In P. Ibarra & B. Tejerina (eds.). Los movimientos sociales. Transformaciones políticas y cambio cultural, 139-163. Madrid: Editorial Trota.

Gamson, W. A. (1992). Talking politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis. An essay on the organization of experience. Boston, M. A.: Northeastern University Press.

Gómez-Román, C. & Sabucedo, J. M. (2014). The importance of political context: Motives to participate in a protest before and after the labor reform in Spain. International Sociology, 1-16.

Goodwin, J., Jasper, J. M. & Polleta, F. (2000). The return of the repressed: The fall and rise of emotions in social movement theory. Mobilization: An International Journal, 5, 65-83.

Hornsey, M. J., Blackwood, L., Louis, W., Fielding, K., Mavor, K., Morton, T., o'Brien, A., Paasonen, K., White, K. M. & White, K. M. (2006). Why do people engage in collective action? Revisiting the role of perceived effectiveness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 1701-1722. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00077.x.

Jarymowicz, M. & Bar-Tal, D. (2006). The dominance of fear over hope in the life of individuals and collectives. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 367-392.

Jasper, M. J. (1997). The art of moral protest. Culture, biography and creativity in social movements. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Jiménez, M. (2011). La normalización de la protesta. El caso de las manifestaciones en España (1980-2008). Catálogo de Publicaciones de la Administración General del Estado, (70). Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Kemper, T. D. (1991). Predicting emotions from social relations. Social Psychology Quarterly, 54, 330-342.

Klandermans, B. (1984). Mobilization and participation: social-psychological explanations of resource mobilization theory. American Sociological Review, 49, 583-600.

Klandermans, B. (1997). The social psychology of protest. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Klandermans, B. (2003). Collective political action. In D.O Sears, L. Huddy & R. Jervis. Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, 670709. N. Y.: Oxford University Press.

Klandermans, B. (2014). Identity politics and politicized identities: Identity processes and the dynamics of protest. Political Psychology, 35, 1-22.

Kriesi, H. (1993). Political mobilization and social change: The Dutch case in comparative perspectiva. England: Avebury, Aldershot.

Le Bon, G. (1983). Psicología de las masas. Madrid: Morata (original, 1895).

Mannarini, T., Roccato, M., Fedi, A. & Rovere, A. (2009). Six factors fostering protest: Predicting participation in locally unwanted land uses movements. Political Psychology, 30, 895-920.

Martín-Baró, I. (1998). Psicología de la liberación. Madrid: Trotta.

McCarthy, J. D. & Zald, M. (1976). Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A partial theory. American Journal of Sociology, 82, 1212-1241.

Meyer, D., & Tarrow, S. (1998). The social movement society: Contentious politics for a new century. Boulder, C. O.: Rowman & Littlefield.

Opp, K. D., Voss, P. & Gern, C. (1995). Origins of a spontaneous revolution: East Germany, 1989. Ann Arbor: The Univesity of Michigan Press.

Páez, D. Javaloy, F., Wlodarczyk, A., Espelt, E. y Rimé, B. (2013). El movimiento 15-M: sus acciones como rituales, compartir social, creencias, valores y emociones. Revista de Psicología Social, 28, 19-33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1174/021347413804756078.

Páez, D., Rimé, B., Basabe, N., Wlodarczyk, A. & Zumeta, L. (2015). Psychosocial effects of perceived emotional synchrony in collective gatherings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108, 711-729. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000014.

Peterson, A., Wahlström, M., Wennerhag, M., Christancho, C. & Sabucedo, J. M. (2012). May day demonstrations in five European countries, Mobilization, 17, 281-300.

Rimé, B. (2012). La compartición social de las emociones. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwe.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. N. Y.: Free Press.

Runciman, W. G. (1966). Relative deprivation and social justice: A study of attitudes to social inequality in twentieth-century England. Berkeley, C. A.: University of California Press.

Sabucedo, J. M., Durán, M. y Alzate, M. (2010). Identidad colectiva movilizada. Revista de Psicología Social, 25, 189-201.

Sabucedo, J. M., Grossi, J. y Fernández, C. (1998). Los movimientos sociales y la creación de un sentido común alternativo. En P. Ibarra y B. Tejerina (eds.). Los movimientos sociales. Transformaciones políticas y cambio cultural, 165-180. Madrid: Editorial Trota.

Sabucedo, J. M. & Vilas, X. (2014). Anger and positive emotions in political protest. Universitas Psychologica, 13, 829-838.

Sears, D. O., Huddy, L. & Jervis, R. (2003). Oxford handbook of political psychology. USA: Oxford University Press.

Simon, B., & Klandermans, B. (2001). Politicized collective identity. A social psychological analysis. American Psychologist, 56, 319-331.

Skitka, L. J. (2010). The psychology of moral conviction. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 267-281.

Skitka, L. J., Bauman, C. W. & Sargis, E. G. (2005). Moral conviction: Another contribution to attitude strength or something more? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 895-917.

Smith, E. R. (1993). Social identity and social emotions: Toward new conceptualizations of prejudice. In D. M. Mackie & D. L. Hamilton (eds.). Affect, cognition, and stereotyping: Interactive processes ingroup perception, 297-315. San Diego, C. A.: Academic Press.

Stürmer, S., & Simon, B. (2004). Collective action: Towards a dual pathway model. European Review of Social Psychology, 15, 59-99.

Stürmer, S. & Simon, B. (2009). Pathways to collective protest: calculation, identification, or emotion? A critical analysis of the role of group-based anger in social movement participation. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 681-705.

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & G. William (eds.). Austin psychology of intergroup relations, 7-24. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Tangney, J., Stuewig, J. & Mashek, D. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behaviour. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345-372.

Tanner, C., Medin, D. L. & Iliev, R. (2008). Influence of deontological versus consequentialist orientations on act choices and framing effects: When principles are more important than consequences. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 757-769.

Turner, J. C. & Killian, L. M. (1987). Collective Behaviour (3rd. ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N. Y.: Prentice Hall.

Van Aelst, P. & Walgrave, S. (2001). Who is that (wo)man in the street? From the normalization of protest to the normalization of the protester. European Journal of Political Research, 39, 461-486.

Van Stekelenburg, J. & Klandermans, B. (2010). The social psychology of protest. Sociopedia. isa, 1- 13.

Van Stekelenburg, J., Klandermans, B. & van Dijk, W. (2009). Context matters: Explaining how and why mobilizing context influences motivational dynamics. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 815-838. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01626.x.

Van Stekelenburg, J., Klandermans, B. & van Dijk, W. W. (2011). Combining motivations and emotion: The motivational dynamics of protest participation. Revista de Psicología Social, 26, 91-104. doi: https://doi.org/10.1174/021347411794078426.

Van Stekelenburg, J., Walgrave, S., Klandermans, B. & Verhulst, J. (2012). Contextualiszing Contestation. Framework, desing and data. Mobilization, 17, 249-262.

Van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T. & Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 504-535. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504.

Van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T. & Spears, R. (2011). The return of moral motivation in predicting collective action against collective disadvantage. Revista de Psicología Social, 26, 163-176.

Van Zomeren, M. & Spears, R. (2009). Metaphors of Protest: A Classification of Motivations for Collective Action. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 661-679.

Van Zomeren, M., Spears, R. E., Fischer, A. H. & Leach, C. W. (2004). Put your money where your mouth is! Explaining collective action tendencies through group-based anger and group efficacy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 649-664.

Van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T. & Spears, R. (2012). On conviction's collective consequences: Integrating moral conviction with the social identity model of collective action. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51, 52-71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02000.x.

Vilas, X. & Sabucedo, J. M. (2012). Moral obligation: A forgotten dimension in the analysis of collective action. Revista de Psicología Social, 27, 369-375.

Vilas, X. (2010). A influencia da obriga moral e o contexto na acción política colectiva. Unpublished dissertation. España: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela.

Walgrave, S. & Vliegenthart, R. (2012). The Complex Agenda-Setting Power of Protest: Demonstrations, Media, Parliament, Government, and Legislation in Belgium, 1993-2000. Mobilization: An international Quartely, 17, 129-156.

Wolpe, J. (1958). Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

License

Diversitas Journal is under license Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)